Rediscovering Van Gogh.

An air of mystery and fascination has surrounded Vincent Van Gogh ever since his death. The artist’s work has commanded astronomical sums at auction, and his mental state has been the subject of discussion and debate for over a hundred years. Until today, the only photographs that existed of Van Gogh were from his teenage years. But even these are the subject of debate — are they really of Vincent, or are they of another Van Gogh? A definitive answer remains elusive.

An air of mystery and fascination has surrounded Vincent Van Gogh ever since his death. The artist’s work has commanded astronomical sums at auction, and his mental state has been the subject of discussion and debate for over a hundred years. Until today, the only photographs that existed of Van Gogh were from his teenage years. But even these are the subject of debate — are they really of Vincent, or are they of another Van Gogh? A definitive answer remains elusive.

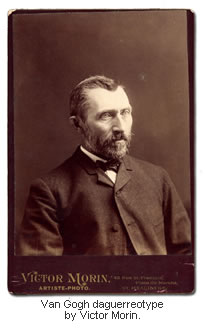

In Brussels around 1886, photographer Victor Morin took a number of photographs of local clergymen. Among these photos was a portrait of a man who bears an uncanny resemblance to the figure in many of Van Gogh’s self-portraits, leading some to speculate that this photo might be of the artist himself.

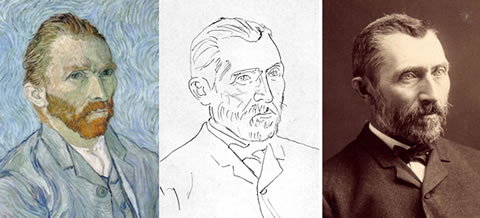

Before this time of this photograph, Vincent’s self portraits were obviously “eyeballed” (to commandeer David Hockney’s phrase) and did not have a strong sense of realism. However, subsequent self-portraits were as close to photo-realism as impressionist paintings could be. Is it possible that Van Gogh used Morin’s photograph as a guide to painting these new, realistic self-portraits? Some experts now believe that the artist may, in fact, have used the photo along with optical projection as a guide when creating these paintings. This possibility is underscored by the fact that when the Morin photograph and some of Van Gogh’s self portraits are overlaid, the close resemblance is hard to deny. If this newly found photograph does indeed turn out to be of the adult Van Gogh, and if it could be proven that optical projection was used by this great impressionist, the implications could change art history.

***

Without the benefit of electricity and with only a simple piece of glass or a mirror, an artist could create a “camera” which would reflect the image he wanted to paint onto a canvas or a piece of paper. This is the underlining principle in David Hockney’s Secret Knowledge.

Although Van Gogh’s self-portraits do not have the same photographic verisimilitude as some of the painting examples in Hockney’s book and film, they do pose a similar question: Why were some of Van Gogh’s self-portraits and the portrait of his mother so much more detailed and “real” looking than his other portraits of the time? Because of the impressionistic nature of Van Gogh’s paintings, we can’t take advantage of clues similar to those that Hockney found in some of the paintings of the old masters, such as out-of-focus objects in the paintings similar to those in photographs, or strong lighting features (‘sun on the face’) that would result from the use of a camera obscura — but the remarkable similarities in detail and composition between the paintings and the photos are strong evidence that Van Gogh’s use of some sort of optical aids in these instances can not be easily ruled out.

We took a copy of the painting and overlaid the photograph of Van Gogh’s mother several times, each with increasing transparency. The results were astonishing. The face in the photo and in the painted image are exact matches. Did Van Gogh want such a perfect painting of his mother that he used optics as an aid in tracing the photograph onto canvas?

***

If Van Gogh used optics to trace his image from the photograph, how could he have done it? Techniques for optically transferring an image include using glass (a primitive lens), a concave mirror (another primitive lens), or a camera obscura or camera lucida. Van Gogh could have used any of these to project his photo onto canvas for tracing. Roger Vaughan, of The Camera Lucida Company in Great Britain, sent us a camera lucida to try some experiments for ourselves. We took the camera lucida and used it to make the sketch below from the Van Gogh photograph.

Camera lucida tracing of the Van Gogh photograph laid over the Saint-Rémy self-portrait with 50% opacity. The tracing is directly taken from the photograph except that the right eye was adjusted so that it’s looking at the viewer as in Van Gogh’s many self-portraits.

Note that it would take great skill and talent to take a sketch like this and make a worthwhile painting from it. We do not imply that Van Gogh cheated by using optics or that using optics in any way would diminish his accomplishments. Projection of a source image is merely both a short cut and a way to help assure that everything is in perspective, thus creating a more life-like painting. Using optics is similar to a carpenter using a nail gun rather than a hammer to drive nails —it doesn’t make the carpenter’s work inferior, but it allows it to be completed in less time.

***

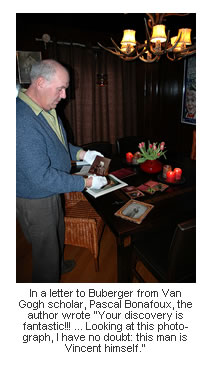

For the last thirty-five years, Joseph Buberger’s vocation has been the history of photography. His studies include most of the 19th century and early 20th century photographic processes, starting with images done in 1839. Many of the images Buberger has discovered have been published and now belong to major institutions. He has daguerreotypes in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of fine art in Houston, and others.

For the last thirty-five years, Joseph Buberger’s vocation has been the history of photography. His studies include most of the 19th century and early 20th century photographic processes, starting with images done in 1839. Many of the images Buberger has discovered have been published and now belong to major institutions. He has daguerreotypes in the collection of the National Portrait Gallery, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of fine art in Houston, and others.

Twenty years ago, Buberger became involved in identifying photographs of well-know people in history. He came across a daguerreotype of Ulysses S. Grant, a younger, different looking Grant than the one we are familiar with from the fifty-dollar bill. His job was to authenticate the photo.

Alan Phillips, a friend of Buberger, was one of the first people involved in creating a forensic overlay of the Grant photo, (a time-consuming process before the advent of digital tools such as Photoshop). Alan is now the correction-imaging manager at the Wadsworth Atheneum, the oldest public art museum in America.

When the Van Gogh photograph came into Buberger’s hands, Philips was already doing the initial forensic work. These results convinced Buberger that this indeed was a photograph of Vincent Van Gogh. Subsequently, Buberger exhibited the Van Gogh photograph at the Seton Gallery University of New Haven in the Henry Lee Institute of Forensic Sciences. Dr. Albert Harper, the Executive Director of the Henry Lee Institute of Forensic Sciences, is also an investigator specializing in forensic anthropology. Dr. Harper sponsored the exhibition, as it is his belief that the photograph is indeed that of Vincent Van Gogh.

The Van Gogh photograph, 4 ½ x 6 ½” has been authenticated as being taken between the years of 1885 and 1890 based on the thickness of the cabinet card as well as the materials that were used from that period. One of the first experiments was to take a self-portrait sketch of Van Gogh (Paris, summer 1887, lead pencil and India Ink on paper, 31.6 x 24.1 cm, Amsterdam) and overlay the drawing with the photograph. The two were a close match.

In a letter to Buberger from Van Gogh scholar Pascal Bonafoux, author of the quintessential tome Van Gogh: Self Portraits, Bonafoux writes, “Your discovery is fantastic!!! … Looking at this photograph, I have no doubt: this man is Vincent himself.” “But,” author of The Van Gogh Files, Ken Wilkie asks, “how did this photograph end up in the archive of a French-Canadian photographer [Victor Morin]?”

Where did this photograph come from? An antique dealer in Massachusetts purchased an album of photographs by the late Morin. These photographs consisted mainly of clergymen, and the album was taken apart and the photos sold separately. While artist Tom Stanford was thumbing through the photos in the dealer’s shop, he recognized the photo of Van Gogh immediately. He purchased it for one dollar. How did Quebec-based photographer Victor Morin shoot a photo of Vincent Van Gogh? And what was Van Gogh’s photo doing among photos of clergymen? These are two questions we will return to in part two of our article in the next issue of Seventh Hour Blues.

No comments:

Post a Comment